TL;DR

A battery is essentially a chemical reaction waiting to happen. Although it doesn’t contain any miles, we are all guilty of thinking of battery capacity in terms of “miles.” That’s equal part laziness and human nature because, at the end of the day, miles are what matters in any vehicle, no matter what is propelling it down the road.

Interestingly, I don’t recall thinking of “miles remaining in the tank” when I drove a gas car; instead, as I started to get below half a tank, I would refer to the remaining capacity as less than half a tank, less than a quarter of a tank, less than an eighth, and finally, “running on fumes.” But I’m as guilty as the next person of thinking in terms of “miles in my battery” until I need to plug in.

Of course, a battery doesn’t hold miles any more than a gas tank holds miles.

The Nitty Gritty Details Regarding EV Battery Capacity and Miles

I write “batteries don’t hold miles” because a common complaint among new EV owners is: “My EV is rated for 300 miles, but it only shows 260 miles and it’s at 100% SOC (state of charge). I took it to the dealer, and they said this is normal. Help! Is there something wrong with my new car?!?!?!” A similar observation is: “Last night, my car said it had 280 miles, but now it says it has 270!” So what’s the deal with EV battery capacity? I have two anecdotes to share on this topic to serve as a reminder of the nuances of driving electric and caring a bit too much about the guess-o-meter’s miles estimate.

My first anecdote is about my garage—it’s a thermodynamic wonder. On mornings when the night has been clear with little wind, the inside of the garage can be 10℉, sometimes 20℉, cooler than the outside air. On one such morning, I unplugged my electric car, and the number of miles estimated was 299. I drove it less than a mile and parked it in the full sun for several hours while running an errand. When I returned to the car, the number of miles estimated was 313. Just by having the car work on its suntan, I gained 14 miles.

Perhaps more interesting was a recent trip spent driving home from Los Angeles to the San Francisco Bay Area in my wife’s Ioniq 5. Some background information for you: my wife has a high-pressure job in the city, and she can occasionally drive like all of her work-related stress is relieved by applying her foot to the accelerator. On the other hand, I retired a few months ago, and the most stressful thing I have on my plate during the week is deciding whether to go to the gym before lunch or wait until late afternoon.

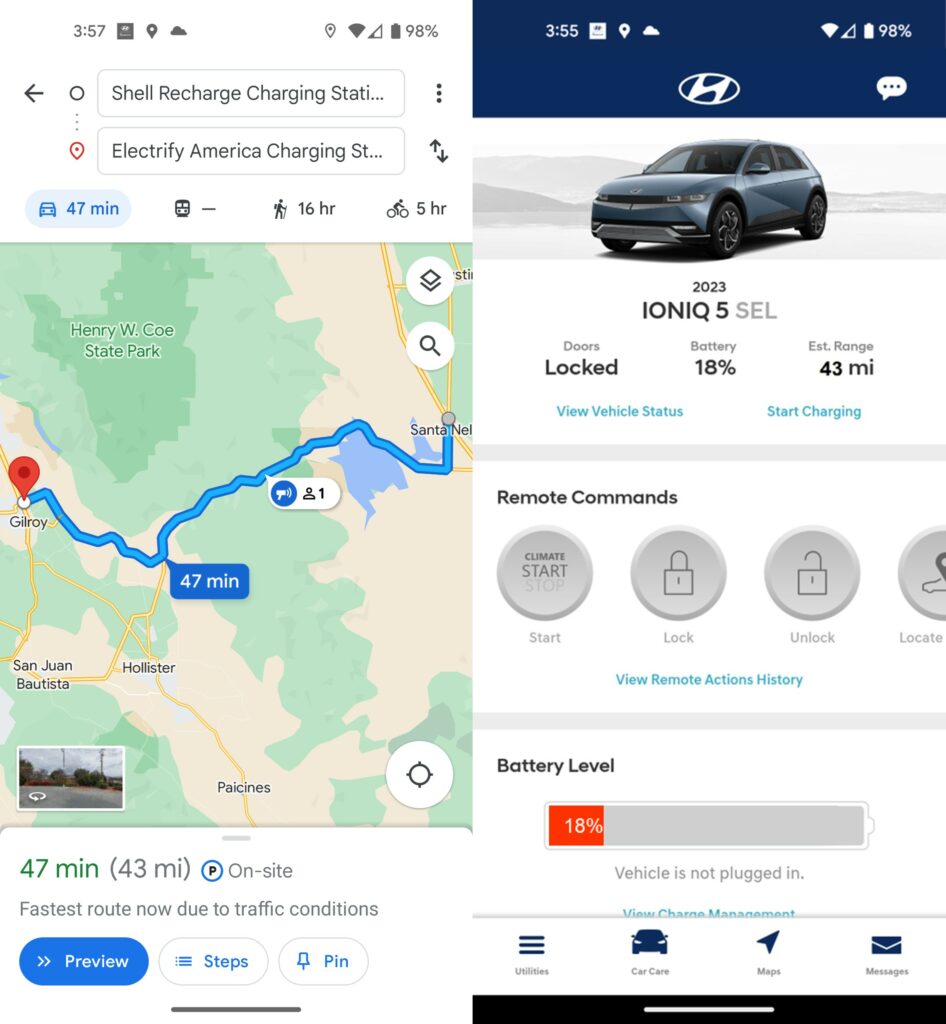

I had planned the charging stops for our LA-to-home drive using ABRP. We’ve done this trip before with only one charge stop, but since we left LA with only 50% SOC, two stops would be required this time around. My wife had been driving as we pulled into our second charging location. That’s when I realized the charging location ABRP routed us to wasn’t one belonging to (our preferred) Electrify America (EA). The GOM showed 43 miles “in the tank,” and the next EA charging location was 43 miles (with 1,100 feet of ascent/descent) away. But I knew the EV battery doesn’t hold miles.

There is an (in)famous YouTube video demonstrating how the more you mess around, the more you find out. Except it is a bit more NSFW than that. If you’re willing to accept wounded pride and the possibility of calling AAA for a tow, please try this at home. While there aren’t 43 miles in the battery, there is 18% SOC remaining. Wanna find out just how far those 43 miles really go? Screenshots by John Higham.

Our Ioniq 5 came with free EA charging, and while getting a free charge was part of the allure to risk going to the next station, food options at our current location were pretty slim, and the preferred EA station was located at the Gilroy Factory Outlets with lots of food options.

The rational thing to do would have been to simply charge where we were, but where’s the challenge in that? I hadn’t yet pushed the Hyundai to its limit and knew the worst thing that could happen was a self-inflicted injury to my pride and an embarrassing call to AAA to haul my butt to the next EA station. So we went for the free charge/better food option.

But we also made a driver change. At the risk of irritating everyone on the interstate, I know I can drive more efficiently than my wife can—because when stretching electrons is on the line, I can be zen behind the wheel vis-a-vis my spouse trying to (literally) get ahead as if office politics translates directly to I-5 traffic. We not only made it to the Gilroy Factory Outlet EA fast chargers, but with two miles to spare.

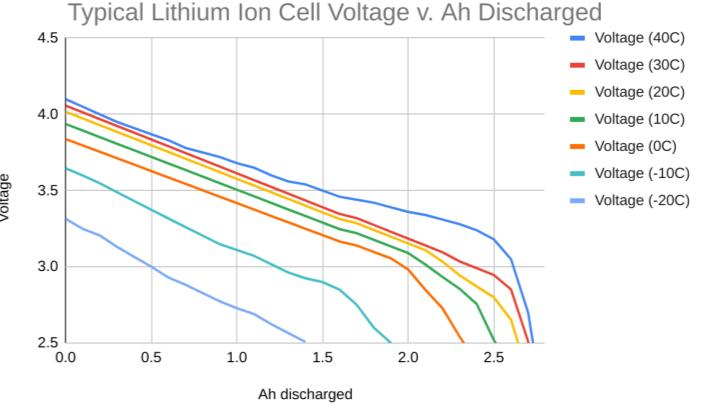

My point in all this is that the saying “your mileage may vary” not only still applies when driving electric, but also with things as simple as battery temperature affect your range. In both cases, no new energy was supplied to the battery, but in both cases, something changed to make miles “appear” seemingly from thin air. In the first case, the temperature of the battery went up, which increased cell voltage. In the second case, a change in driving tactics increased the car’s efficiency.

We’ve seen this graph before in the column on the GOM. A battery is made up of cells, and cell manufacturers rate capacity in terms of Amp-hours (Ah). High school physics teaches that power (in Watts) is voltage times current (measured in Amps). What’s important here is that without adding any Ah to a cell (or battery), you can increase its power output (in Watts) by increasing its temperature. The graph shows that this effect can be drastic as temperatures drop below 0° C. Graph provided by John Higham as interpreted from sources online.

You don’t fill up your battery with miles any more than you fill up your gas tank with miles. We’ve reviewed the variables of what goes into the estimate of an EV’s range when this column discussed the GOM; a quick refresher is that when you see the number of miles available on your EV’s dash, what you’re actually seeing is the product of two separate estimates. The first estimate is of the energy in the battery in kWh (kiloWatt-hours). The second estimate is a prediction of the future efficiency of the car based on past performance. The takeaway from this conversation is that the estimate of the amount of energy stored in your battery as measured in kWh is pretty good. But the prediction of future efficiency is part science and part séance.

Next week we will discuss etiquette at public charging infrastructure. It’s a thing, and you should definitely know about it.

0 Comments